Four Shifts and Innovations in Sharing and Leveraging Private Assets and Expertise for the Public Good

For years, public-private partnerships (PPPs) have promised to help governments do more for less. Yet, the discussion and experimentation surrounding PPPs often focus on outdated models and narratives, and the field of experimentation has not fully embraced the opportunities provided by an increasingly networked and data-rich private sector.

Private-sector actors (including businesses and NGOs) have expertise and assets that, if brought to bear in collaboration with the public sector, could spur progress in addressing public problems or providing public services. Challenges to date have largely involved the identification of effective and legitimate means for unlocking the public value of private-sector expertise and assets. Those interested in creating public value through PPPs are faced with a number of questions, including:

- How do we broaden and deepen our understanding of PPPs in the 21st Century?

- How can we innovate and improve the ways that PPPs tap into private-sector assets and expertise for the public good?

- How do we connect actors in the PPP space with open governance developments and practices, especially given that PPPs have not played a major role in the governance innovation space to date?

The PPP Knowledge Lab defines a PPP as a “long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility and remuneration is linked to performance.”

Typically PPPs develop or manage physical infrastructures such as roads, telecom networks, energy plants or health facilities. More recently, both the public and private sector have experienced major transformations in how they address complex and interdependent problems.

To maximize the value of PPPs, we don’t just need new tools or experiments but new models for using assets and expertise in different sectors. We need to bring that capacity to public problems.

At the latest convening of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Opening Governance, Network members and experts from across the field tried to chart this new course by exploring questions about the future of PPPs.

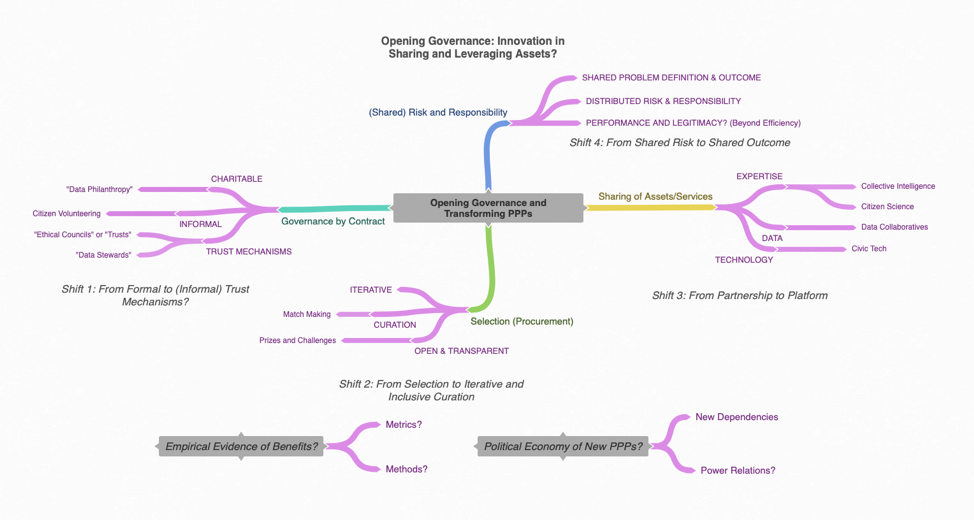

The group explored the new research and thinking that enables many new types of collaboration beyond the typical “contract” based approaches. Through their discussions, Network members identified four shifts representing ways that cross-sector collaboration could evolve in the future:

- From Formal to Informal Trust Mechanisms;

- From Selection to Iterative and Inclusive Curation;

- From Partnership to Platform; and

- From Shared Risk to Shared Outcome.

Shift 1: From Formal to Informal Trust Mechanisms

Traditionally, PPPs are built on contractual and formal relationships. Government and business decide they want something the other side has and sign an agreement guaranteeing they will provide it to the other.

The approach calls for officials to outline their roles in specific, tangible terms, but other models exist that utilize different assets and less formal structures

For instance, data collaboratives, where companies publish or donate datasets for outside collaboration, is an increasingly common way of gaining new value from data. Companies might recognize their large caches of information can be used in new ways by outside actors.

Citizen volunteering, especially in citizen science projects, is another way to proactively create new value using data. Instead of tethering itself to another actor, government or industry can work with private citizens to find new ways to use existing datasets or collect new ones.

Lastly, officials can use mechanisms, like ethical councils, trusts, and data stewardship, to govern a PPP and help it respond to dynamic and evolving events. For its global data competition, Orange Telecom set up an ethical council composed of international experts to help it navigate moral questions that arose.

Shift 2: From Selection to Iterative and Inclusive Curation

A second discussed shift is the move from selection to iteration and inclusive curation. In the contract structure, roles are set at the beginning of the project, in danger of becoming calcified or corroded if the project focus changes.

Today, PPPs are moving toward more agile supply-and-demand approaches to allow them to bring needed assets and capacity to bear when necessary instead of relying on a decades-long contract with a private vendor. Projects like GovLab and UNICEF’s Gender and Urban Mobility initiative recognize the ways in which collaborations can change and develop over time.

Shift 3: From Partnership to Platform

Third, PPPs are increasingly about providing a platform through which assets and services can be shared, not just achieving some explicit reciprocal goals.

Initiatives like Beeline Crowdsourced Bus Service allow citizens to work collectively to share intelligence and add to a project’s scientific capacity. They can also allow multiple groups to share datasets for the public good or exploit new technologies for civic good.

As data becomes a more prominent asset for both the public and private sector, platforms that intake and utilize the data become fertile grounds for partnership.

Shift 4: From Shared Risk to Shared Outcome

Finally, as described by the Intersector Project among others, PPPs are not without risks for all parties – including intended beneficiaries. Increasingly, new conceptions of PPPs are aimed at creating shared outcomes and jointly working toward opportunities rather than simply distributing and sharing the risks involved in a project. Risks and challenges exist across a project’s lifecycle but their mitigation (and the mitigation of public scrutiny of participating entities) cannot be a goal in and of itself.

The current move toward a more collaborative approach targeted at creating shared outcomes, demonstrates officials’ growing recognition of the need for understanding the problem and working toward a mutually beneficial outcome.

Going forward – Remaining Questions and Challenges

The MacArthur Foundation Research Network meeting is only one part of a larger conversation ongoing within the data field. While PPPs are often a tool to open governance and create new opportunities, we are only now understanding the ways in which they can be used effectively and legitimately.

Questions remain, though, on how to ensure projects remain sustainable, ensuring that initial philanthropic feelings are not crushed when subject to financial pressures. Moreover, longstanding and emergent challenges still need to be addressed if the next generation of PPPs is going to achieve its potential and avoid an array of potential harms.

Some of those challenges include ensuring PPPs are not a guise for privatization, preventing information disclosures (particularly when personal data is at play), and guaranteeing a PPP accounts for (and does not exacerbate) existing power dynamics.

The next few weeks we will translate the above into a more detailed research agenda. In the meantime please send us your suggestions, recommendations (for readings), interests to be involved and questions to be included moving forward (stefaan at thegovlab.org).