Government reformers and advocates believe that two contemporary phenomena hold the potential to change how people engage with governments at all levels and how they are served by public agencies. The first is data. There is more of it than ever before and there are more effective tools for sharing it, analyzing it, and organizing it. This creates new service-delivery possibilities for government through use of data that government agencies themselves collect and generate. The second is public desire to make government more responsive, transparent and effective in serving citizens — an impulse driven by tight budgets and declining citizen trust in government.

A third factor is also inspiring some level of hope about the impact of releasing large volumes of data. Some believe that clever commercial and social entrepreneurs will be able to find ways to exploit the data and create new businesses or policy solutions once they can have access to the vast stores of information governments collect – much the way weather forecasting companies use government data to create products and services that help tens of millions of people.

The upshot has been the appearance of a variety of “open data” and “open government” initiatives across various levels of government in the United States. They aspire to use data as a lever to improve government performance and encourage warmer citizens’ attitudes toward government.

Key public opinion findings

The Pew Research Center conducted a national survey of 3,212 adults last winter designed to benchmark public sentiment about the government initiatives that use data to cultivate the public square. The survey was done in association with the John S. And James L. Knight Foundation and the findings included:

As open data and open government initiatives get underway, most Americans are still largely engaged in “e-Gov 1.0” online activities, with far fewer attuned to “Data-Gov 2.0” initiatives that involve agencies sharing data online for public use.

The survey showed that 65% of Americans in the prior 12 months have used the internet to find data or information pertaining to government.

In this early phase of the drive for open government and open data, people’s activities tend to be simple. Their connection to open data could be as routine as finding out the hours of a local park; or it could be transactional, such as paying a fine or renewing a license.

At the same time, minorities of Americans say they pay a lot of attention to how governments share data with the public and relatively few say they are aware of examples where government has done a good (or bad) job sharing data. Less than one quarter use government data to monitor how government performs in several different domains.

Few Americans think governments are very effective in sharing data they collect with the public:

- Just 5% say the federal government does this very effectively, with another 39% saying the federal government does this somewhat effectively.

- 5% say state governments share data very effectively, with another 44% saying somewhat effectively.

- 7% say local governments share data very effectively, with another 45% responding somewhat effectively.

Relatively few Americans reported using government data sources for monitoring what is going on in their communities:

- 20% have used government sources to find information about student or teacher performance.

- 17% have used government sources to look for information on the performance of hospitals or health care providers.

- 7% have used government sources to find out about contracts between government agencies and outside firms.

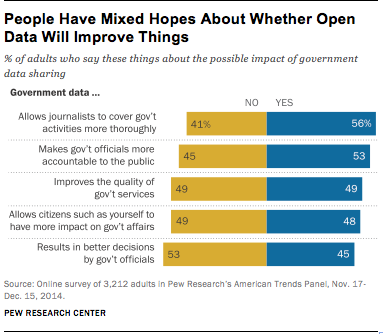

Americans have mixed hopes about government data initiatives. People see the potential in these initiatives as a force to improve government accountability. However, the verdict is mixed as to whether government data initiatives will improve government performance.

When looking at government performance, however, people are less optimistic, with less than half of Americans saying open data can help the quality of government services or officials’ decisions. Proponents of open data hope that a variety of benefits might emerge from greater transparency about government activities, from more public accountability to better customer service. Majorities are hopeful that open data can help journalists cover government more thoroughly (56% do) and 53% say open data can make government officials more accountable. Combining those who respond affirmatively to these propositions means that 66% of Americans harbor hopes that open data will improve government accountability.

Additionally, 50% say they think the data the government provides to the public helps businesses create new products and services.

People’s baseline level of trust in government strongly shapes how they view the possible impact of open data and open government initiatives on how government functions.

In this survey, 23% of Americans say they trust the federal government to do the right thing at least most of the time. This trusting minority of Americans is much more likely than others to see the potential benefits of government data initiatives:

- 76% of those who generally trust the federal government say government data can help government officials be more accountable.

- 73% believe government data can help journalists cover government more thoroughly.

- 71% back the idea that government data results in better government decisions.

- 70% agree with the notion that government data can enable people to have a greater impact on government affairs.

- 69% say government data can improve the quality of government services.

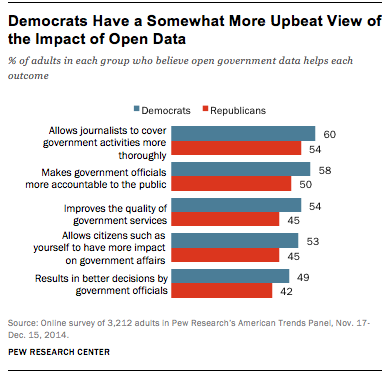

Americans’ perspectives on trusting government are shaped strongly by partisan affiliation, which in turn makes a difference in attitudes about the impacts of government data initiatives.

Those with different partisan views have different notions about whether they trust government. Some 31% of those identifying as Democrats (or leaning that way) say they trust the federal government to do the right thing most of the time, compared with 15% of those identifying as Republicans (or leaning that way).

The differences between Democrats and Republicans views on the possible impact of open government initiatives are highlighted in the nearby chart.

Americans are for the most part comfortable with government sharing online data about their communities, although they sound cautionary notes when the data hits close to home.

People’s comfort with government data-sharing varies across a range of topics:

- 82% of adults say they are comfortable with government sharing data online about the health and safety records of restaurants.

- 62% are okay with government sharing information about criminal records of individual citizens online.

- 60% can accept government sharing data about the performance of individual teachers at schools online.

- 54% are comfortable with government sharing data about real estate transactions online.

- Only 22% are comfortable with government sharing information about mortgages of individual homeowners online.

Where does this leave things?

For stakeholders hopeful that open data and open government can have an impact, the data provide a mixed message. About 17% of adults see the potential of open data pretty clearly. A slightly greater number, 20%, are relatively familiar with government data initiatives, but remain wary that these initiatives will have much impact on government performance.

Some 27% see the appeal of open government-open data, but for whatever reason do not use the tools that much. And 36% can be described as having an uncertain outlook because they are not now interested or engaged with these issues. To the degree they might ponder open-data initiatives, they seem to be wondering whether these initiatives can make a difference and are reluctant to start exploring something for which they see little potential impact.

A potentially significant barrier to government data initiatives lies in the connection between trust in government and skepticism among some citizens about whether these initiatives will bolster government performance. The greater a person’s trust in government, the greater the likelihood she believes government data initiatives will improve government performance. That sets up a chicken-and-egg dilemma. Do government data initiatives spark high levels of trust in government? Or do low levels of trust in government attenuate the benefits to civic engagement that are a motive for many government data initiatives? In highlighting this dynamic, this research points to the challenges and possibilities in ongoing efforts in the open data and open government arena.

After looking at these findings, Jon Sotsky, the Knight Foundation’s director for strategy and assessment argued similarly, “While most Americans use the internet to intermittently access government information or services, few have considered how increasing the availability and utility of government data could impact their lives. The split feelings about whether openly publishing more government data even has the potential to improve government accountability primarily reflects existing low levels of trust in government, which is ironic because open data initiatives largely aim to increase this trust.”